Environmental Sustainability Spotlight

Environmental Sustainability Spotlight: University of Toronto Trash Team

We have all seen heart-wrenching photos of plastic pollution in the oceans; be it fish stuck in plastic straps, seas turtles trying to eat a plastic bag, or dead whales with tons of single-use plastics in their guts. It’s clear that we need to do more than give up our plastic straws and cups. A group of researchers, students, educators and volunteers in Toronto have been tackling this complex issue at all fronts.

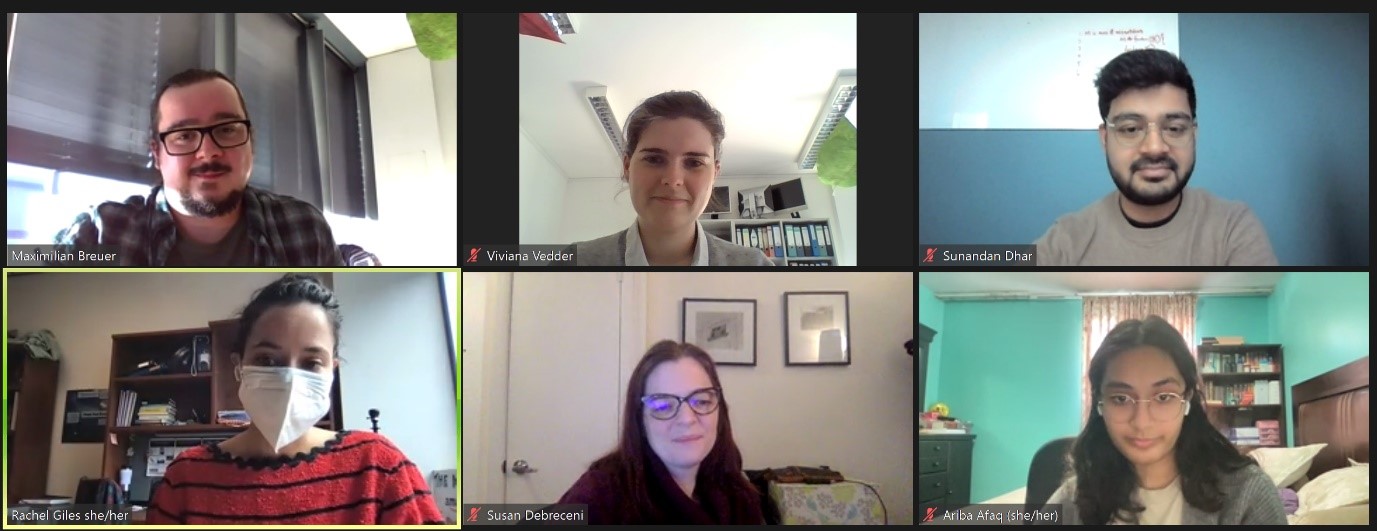

The University of Toronto Trash Team was founded in 2017 in close collaboration with Dr Chelsea Rochman’s lab. A founding member and program lead, Susan Debreceni recalls, “it was initially a small team with a common interest in reducing waste but also engaging with the community”. Over the past 5 years, it has grown into a vibrant science-based outreach group aiming to reduce plastic pollution while also increasing waste literacy. While they are based in Toronto, they have integrated their efforts with groups around the world through the International Trash Trap Network in collaboration with Ocean Conservancy.

We spoke to Susan and two other members of the U of T Trash Team: Rachel Giles, a long-time volunteer and PhD candidate in the Rochman lab, and Ariba Afaq, an undergraduate student volunteering with the team over the past year.

For Rachel, working with the Trash Team has gone hand-in-hand with her research. She started volunteering with the group from its earliest days, and this helped inform her decision to pursue a PhD in the Rochman lab. “I was figuring out what to do after my undergraduate degree. I wanted to be involved in scientific research in a way that benefits communities and is communicated to the general public”. Her research work has taken her from Toronto to Vietnam, analysing aquatic ecosystems in riverbeds while also helping set up trash traps in those same rivers. She studies the impact of stressors such as microplastics and contaminants on invertebrate species living at the bottom of streams. Plastics from car tires or de-icing salt from roads can run off into streams and end up in lakes or the sea. Such anthropogenic pollutants significantly impact organisms such as mussels, worms, crayfish and insect larvae, which form a crucial part of the aquatic biodiversity and indicate the health of the ecosystem as a whole.

Ariba was introduced to the Trash Team through her sister, already a volunteer, and through a course taught by Dr Rochman at the University of Toronto. She spent some time helping quantify and characterise the waste from a trash trap. “I knew that microplastics were an issue, but I didn’t know how bad it was until I started working on the field and picking up thousands of pieces of plastic every day”. Her experience in the field inspired her to delve into the role of policy decisions to help tackle the issue. She has authored briefs that report the impact of the Trash Team’s projects and set out ways in which policy changes can help solve the problem.

Trapping trash

Trash traps are exactly what they sound like, any device designed to trap litter and divert them from local ecosystems. Floating aquatic pollutants are trapped using containers secured in place in a river or harbour. They come in various shapes and sizes, according to the specific requirements of the site. Those used in Toronto are called Seabins, which are cylindrical baskets about half a metre in diameter, and pump water into the device to capture floating litter before they flow into Lake Ontario. Susan notes that the Trash Team started out “with the specific idea to bring this innovative technology to Toronto to clean up waste”.

A Seabin installed in the Toronto harbour to trap floating litter

Ariba reports that “a single trap can divert an average of 30 grams of anthropogenic debris per day, translating into 209 pieces of small plastic items”. There are six Seabins in the Toronto harbour, capable of trapping more than 33 kg of litter over a single boating season. Microplastics (smaller than 5 mm in size) are more difficult to capture using traditional trash traps. The Rochman lab and other groups are currently exploring the potential use of aquatic plants and algae to trap aquatic microplastics more effectively.

Setting up a trash trap in the Song Hong River in Vietnam provided a very different challenge. Working with a local organisation, they surveyed different sites along the river and characterised the litter to identify ideal locations for a trash trap. The river is deep and wide, with larger pieces of litter that would clog up a Seabin very quickly. The solution was to build a large trap using local materials. Rachel describes that “it takes advantage the river’s natural direction of flow and a set of arms, or boons, stretches the width of the river and brings the trash into the trap. [The trap] itself is essentially a giant metal basket that is kept floating and attached in place”. Such a custom-built trap reduces the cost and can be replicated easily at other sites.

A custom-built trash trap for the Song Hong River in Vietnam to divert large pieces of litter

What to do with the trash?

Trash traps are emptied at regular intervals by volunteers from the local community. The volunteers sort the trash, separating those items that can be recycled. The system set out by the Trash Team at Toronto has been replicated by other groups that are a part of the International Trash Trap Network. The trap at Vietnam is similarly maintained by locals from Nam Dinh city. They sort the waste by type, identifying the items that can be recycled into plastic pellets and sold to local producers. Rachel explains, “this closes the loop [of plastic usage] and also engages with the communities to get them invested in the technology and in the issue in general.”

This also presents an opportunity to gather data about the quantities and types of litter found at specific sites. The waste found varies by location and time due to varying patterns in human activity. All of this data can be logged on to the International Trash Trap database through an app. In addition to acknowledging the contribution of communities in tackling plastic pollution, the compiled datasheets are open source, allowing scientists and policymakers around the world to access it. This real-world data can also be invaluable while quantifying the ecological impact of plastic pollution or while checking the efficacy of potential solutions.

This is a powerful resource that the team uses to design policy briefs that tackle plastic pollution. Ariba explains that “these documents can target the general public to raise awareness about the problems, but also policy makers to help inform decisions”. Local authorities can look at the evidence to gauge the scale of the issue and to track whether certain policies have been beneficial over time. For example, they can show that the ban on single use plastics is on the right track, or the need to better regulate waste from construction sites to prevent construction-related foam in rivers. These briefs can be sent to specific people who can influence policies, or to the wider public using social media. “Sometimes it can take a disaster to happen before [authorities] realise that something has to be done”, Ariba has learned, “it can be easier to reach out to one person who is influential or has power to make changes”. Over the years, the team has built up connections with key stakeholders and organisations that are passionate about the issue and can facilitate action.

Engaging with communities

Beyond the data, getting local communities involved can be a powerful driver for change. Ariba recalls her experience during field work, “as people walked past, they saw the massive amounts of trash being taken out. It can be shocking to many and helps spread awareness”. Volunteers regularly have conversations with members of the community from all ages and backgrounds. Rachel notes that “it builds up a crowd and the engagement snowballs as more people want to find out about what’s going on”. Not only does it help inform the public about the problem, but it also demonstrates to them that proactive action can help solve it.

While they have been making a measurable impact, Rachel also points out that trash traps cannot solve the problem on their own. “It’s necessary to have solutions from multiple angles… community-based and policy-based approaches to incrementally move towards a plastic-free environment”. The Trash Team has been developing education programs in local schools to increase understanding about plastic pollution, its impact on ecosystems, and potential solutions. Rachel and other members of the team are energised by such outreach activities, “children are much more passionate and have so much vigour than we do! It can be a heavy topic, but kids are much more optimistic when coming up with the solutions”.

Balancing academics and volunteering

We all know how challenging it can be to balance a career in academia with volunteering and outreach. How do the members of the Trash Team do it so well? The answer seems to be an approach based on passion, teamwork and flexibility. Susan explains, “we encourage people to get involved as much or as little as they can manage, in an authentic way that makes them passionate”.

For Rachel and Ariba, their volunteering work has complemented their academic and career interests, but has still required careful time management. Ariba cherishes her field work in the past as it was an opportunity to conduct research while also interacting with the community. As her academic schedule becomes busier, she does not feel the pressure to overburden herself. “You don’t have to do a lot at the same time. I can talk to the team about managing time, they are very understanding”.

Rachel tells us that her involvement has varied at different points of her PhD. The support of her supervisor has been crucial, “Chelsea values and encourages outreach work, it was conscious decision to work with her for graduate school because it was important for me to be able to engage with communities along with my research work”. The cooperation of the team has allowed her to constantly stay involved and contribute according to her strengths while enjoying the entire experience.

Looking to the future

Rachel hopes to return to Vietnam before wrapping up her PhD for some more analysis of the impact of aquatic stressors in the Song Hong. She is keen to stay involved with the Trash Team and engage in more community outreach. We are excited to hear that she is also planning to write a children’s book about her work in Vietnam.

Ariba looks forward to being more involved with policy briefs for the Trash team, with an eye on a career in environmental law in the long term. “I’m only in my second year so I know things are going to change. I don’t know [about the future] for sure but I know I will continue to volunteer for the Trash Team”.

The team as whole plans to collaborate with other groups who want to build local trash traps and expand the international network. They are also focussing on creating visual content, from artwork to informative videos, to enhance public engagement and education. We have no doubt that they will continue to inspire us all about how to tackle such a complex environmental issue. Susan shares, “we want to be honest about the scenario, but to come at it with a positive attitude and make positive change”.

We want to thank Susan, Rachel and Ariba for taking the time to share their inspiring stories and insight, and for the amazing work they are doing! Speaking to them has encouraged us to look at the waste coming out of our own labs and to find ways to reduce it. Keep a look out for IZFS Waste Audit that will soon be put out by the Sustainability committee to know how you can be a part of this.

Interview by Dr Maximilian Breuer, Viviana Vedder and Sunandan Dhar

Article written by Sunandan Dhar