Science and Society

Jules Verne, the Natural World and our Future

Classes start this month here in the Southern Hemisphere and like many I dread the looming hours of Zooming and anxiously await my turn to get “stabbed”, hopefully next week. My eyes, tired of the light-emanating screen of the computer, yearn for the reflected light of the printed page, so in the evening I read before going to bed. In my version of escapism I have just finished Jules Verne’s “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea”, in an original print book from years ago. I was shocked to realize that my memory of this story was so tainted by Walt Disney, I had lost all perspective of this tale. I never read the amazing descriptions of the ocean and the natural world, written by a French novelist, poet, and playwright who only traveled in Europe. Furthermore Wiki is correct in stating that Verne is “considered to be an important author in France and most of Europe… His reputation was markedly different in Anglophone regions where he had often been labeled as a writer of genre fiction or children’s books, largely because of the highly abridged and altered translations…”

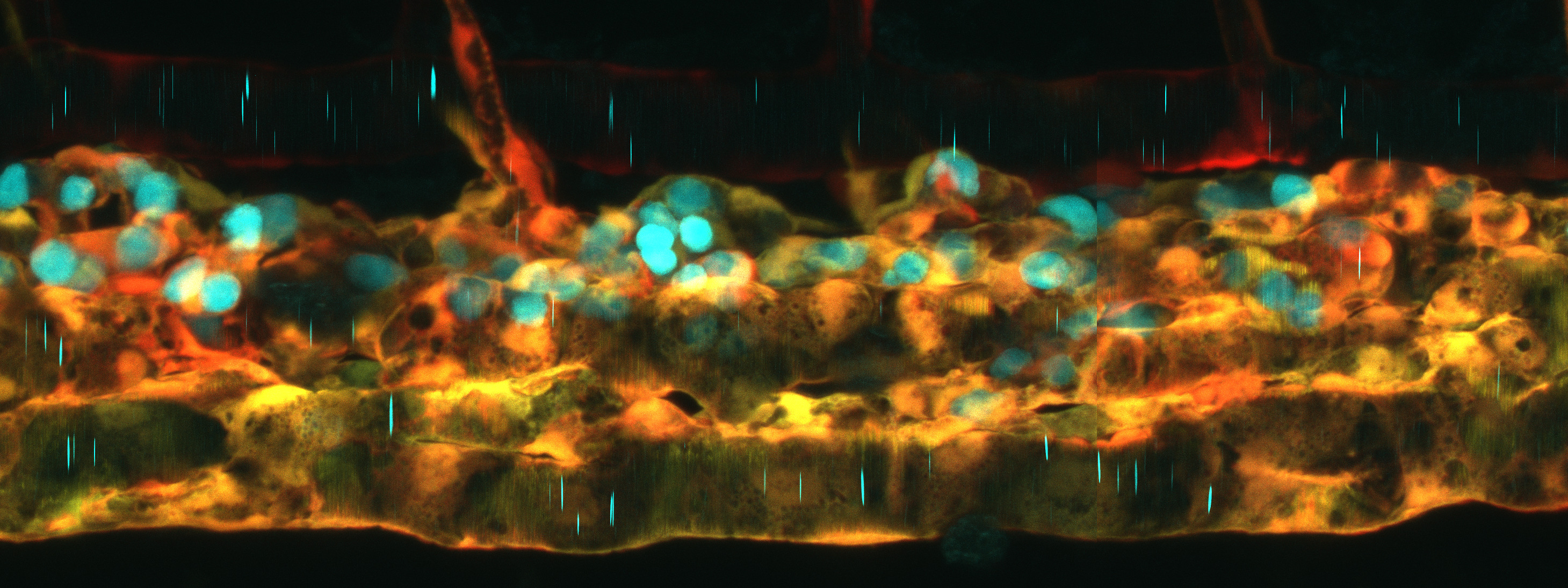

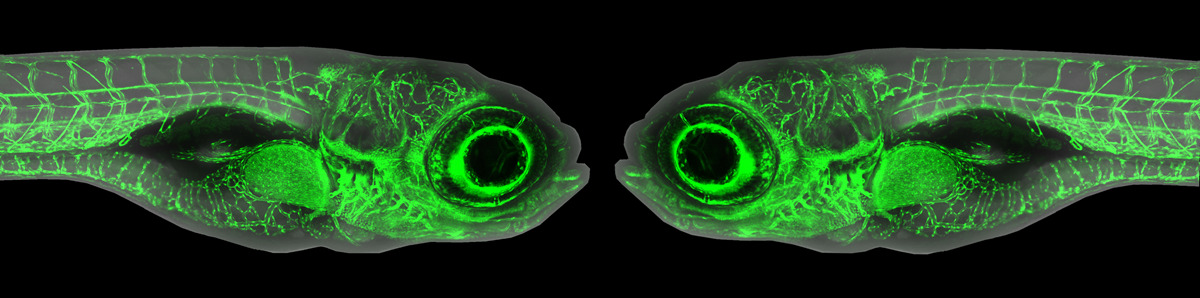

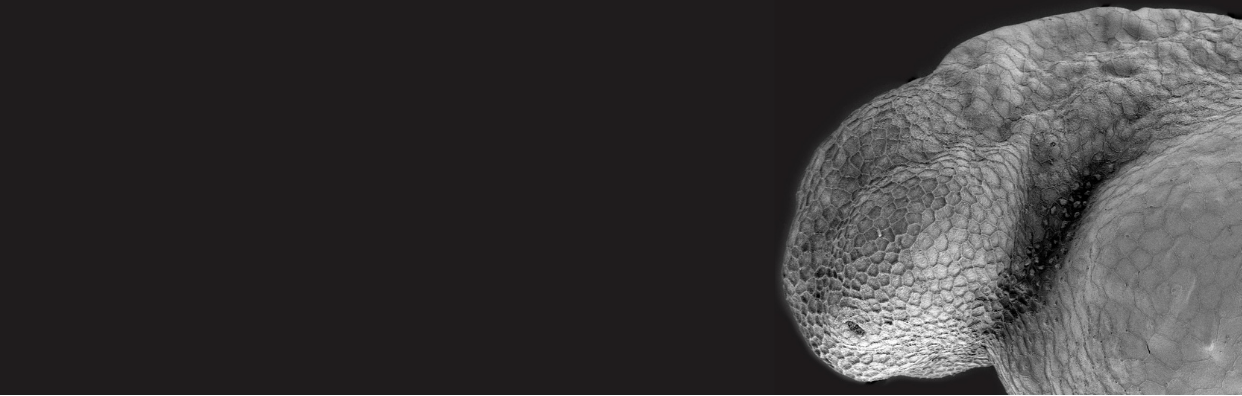

But why Jules Verne’s “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea”? The description of the natural world told through the eyes of Professor Pierre Aronnax a visitor and captive on the submarine Nautilaus with Captain Nemo at the helm, is a marvel. The description talks of the bounty of the whales, of all marine mammals in the South Pole, abundance of seabirds, the penguins, along with a most interesting description of a dugong. Against the dark backdrop of the professor’s situation there is a constant delight and fascination in diversity of creatures and plants he encounters. The story takes place in the 1860s, but now we leap forward to a time where most corners of the world have not only been “discovered” but somehow altered leaving little room for imagination, only for photos. We know that cuttlefish will not ravage a submarine, and importantly we no longer read to create images in our brains, rather we fill them directly from screens. We do not read words, form images and then head off into the natural world to see if that animal really exists, if that flower really is a magnificent hue of blue (like the Mecanopsis poppies of the Himalayas). And as we stare at our screens the deep oceans are warming at an alarming rate, the conveyor belt of the Atlantic Ocean that maintains the European climate and brings nutrient rich cold water to the equator has slowed by 15%. And now scientists have documented what has been only hinted at until recently: animals in the sea are starving to death, the grey whales who normally feed in colder waters before migrating are dying as a result of starvation due lack of prey, thought to be caused by warming Arctic waters where they feed. How will we describe a whale when they are no longer here? What will we, the scientists do? In the end will we be like Pierre Aronnax, a scientist who can ignore all bad while fascinated with the complexity and beauty of what he was observing? Or, will we, researchers in science, use our well-developed problem solving skills to take drastic action?

The purpose of this Science and Society is not to depress everyone (though I am fairly depressed at times), but it is a call to action, a call to rise above the profound sadness and chaos of the pandemic and remember that the greatest challenge is the destruction of the natural world on which we depend. So please write to me (kathleen.whitlock@uv.cl) and tell me a story, tell me what action you are taking especially what you have changed in your lab. I will collect your ideas and suggestions for the next newsletter. I will end with my story about water: here in my region of Chile we are in a severe drought made more terrible by a combination of greed and climate change. With our outreach program we are learning about the amazing properties of water, how to filter water, how to test water, and how to become the “keepers” of the water….to protect this essential resource.

Keep well and treasure what is still here.

Kate

Valparaiso

March 2021